With just a few days to go before the end of COP30 in Belém (Brazil), international negotiations are entering a decisive phase, no longer to determine the place of carbon dioxide removal (CCS) in the global climate framework, but to deploy a now-established framework in concrete terms. After three years of technical consolidation around the implementation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, the central issue is no longer the integration of EDC, but operational guarantees, financing mechanisms and the fair distribution of benefits for the countries of the South.

Belém will also be the first COP to host a pavilion entirely dedicated to the CDR, initiated by CDR30As a further sign of its growing institutional recognition, for AFEN this COP marks the beginning of the implementation phase: carbon removal is moving from the stage of technological promise to that of governance, traceability and structured financing.

The question then becomes one of credibility on a large scale: how can we distinguish sustainable removal from conventional offsets? How can CDR technologies be integrated into Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) without diluting the integrity of the balance sheets? And how can the 300 billion USD/year of the New Collective Quantified Target (NCQG) be effectively channelled into storage, monitoring and risk management infrastructures?

To fully grasp the issues at stake at Belém, we need to look back at the trajectory that has gradually placed the CDR at the heart of international climate grammar, a trajectory made up of trial and error, legal clarifications and major structural advances, now ready for implementation.

From Kyoto to Dubai: the gradual integration of the CDR into the international climate framework

The integration of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) into international climate governance has begun with the Kyoto Protocol (COP3, 1997). The LULUCF (Land Use, Land-Use Change and Forestry) scheme recognizes removals by forests and soils: Removal Units (RMU) can be counted when a LULUCF activity effectively removes CO₂ from the atmosphere. Each RMU is equivalent to one tonne of CO₂ removed, making it possible to increase the national quota of authorized emissions. This mechanism, although marginal on a global scale, has had a notable weight in the accounting of industrialized countries: during the first commitment period (2008-2012), credits from forest management represented about 2.3 % of developed countries' total emissions, almost half their average reduction target of 4.4 % compared with 1990. In other words, a significant proportion of the "reduction" recorded (53%) came from forest carbon sinks rather than actual reductions in industrial emissions.

In project mechanisms, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), introduced by Article 12 of the Kyoto Protocol, has authorized afforestation and reforestation projects in developing countries since the early 2000s. These deliver temporary credits (tCER and lCER) to take account of the risk of non-permanence: the credits expire and must be replaced at maturity to compensate for any loss of stored carbon (in the event of fire or logging, for example). In practice, this opening has remained marginal: in 2012, fewer than 40 forestry projects had been registeredand only one had issued credits, so CDR share under Kyoto remained symbolic.

The Marrakech Accords (COP7, 2001) set out the technical details of the CDM and officially authorized forestry credits from afforestation/reforestation projects, while establishing a strict framework: Annex I countries can only use these CER credits up to a maximum of 1 % of their 1990 emissions multiplied by five over the first commitment period (2008-2012). This ceiling reflects the Parties' prudence in the face of uncertainties about permanence and the risk of environmental non-integrity. The LULUCF framework therefore remains limited to "natural sinks", and "technological" CDR projects, such as capture and storage (CCS), are only admitted to the CDM after Durban (COP17, 2011), subject to post-project monitoring and liability in the event of leakage.

The political turning point came with the Paris Agreement (COP21, 2015). Its Article 4 calls for a "balance between anthropogenic emissions and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases" to be achieved in the second half of the century. This formulation legally enshrines carbon neutrality and explicitly legitimizes CDR activities, whether natural or technological. Article 5 reinforces this framework by committing Parties to "conserving and enhancing GHG sinks and reservoirs", thus providing the accounting basis for including CDR in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and in overall progress assessments.

The following years consolidated this recognition. COP24 in Katowice (2018) adopts the Katowice Climate Package, setting out the rules for transparency in post-2020 climate monitoring: states must report their emissions, removals and reduction actions in a harmonized way, creating the measurement and verification framework essential to the CDR. The IPCC special report on +1.5°C (2018) points out, moreover, that all scenarios compatible with this objective require the removal of between 100 and 1,000 billion tonnes of CO₂ by 2100.

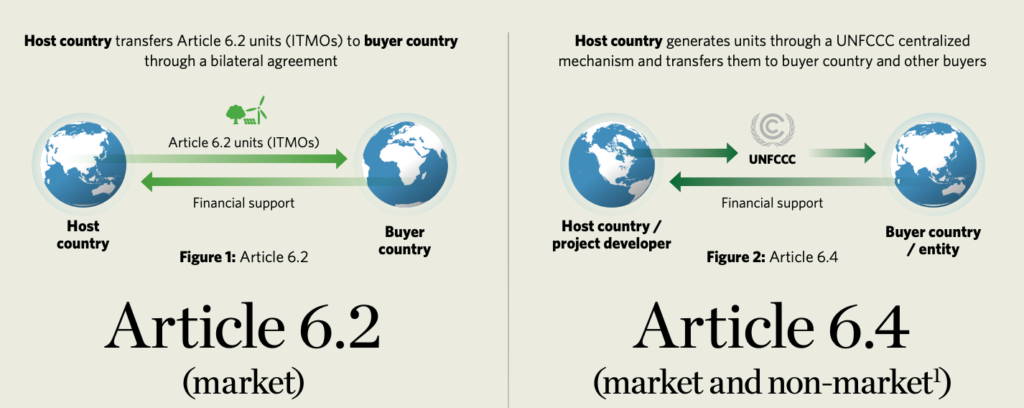

In Glasgow (COP26, 2021), the Parties will finally finalize the rules for implementing Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which defines carbon cooperation mechanisms. This new architecture is structured around two components:

- Article 6.2, enabling bilateral or multilateral exchanges of units known as ITMOs (Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes)

- Article 6.4establishing a centralized UN mechanism, the future Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM), designed to credit both CO₂ reductions and removals according to approved methodologies.

Glasgow's decisions also specify safeguards Each transfer must give rise to a corresponding adjustment to avoid double-counting, 5 % of credits are transferred to the Adaptation Fund, and 2 % are cancelled as additional global mitigation (OMGE). These rules, adopted after more than five years of negotiations, lay the institutional foundation that would, a few years later, enable CO₂ removals to be explicitly integrated into international market mechanisms.

Article 6: architecture, tensions and implementation for CDR

The years 2022-2024 were dominated by debates on environmental integrity and the conditions for implementing Article 6.

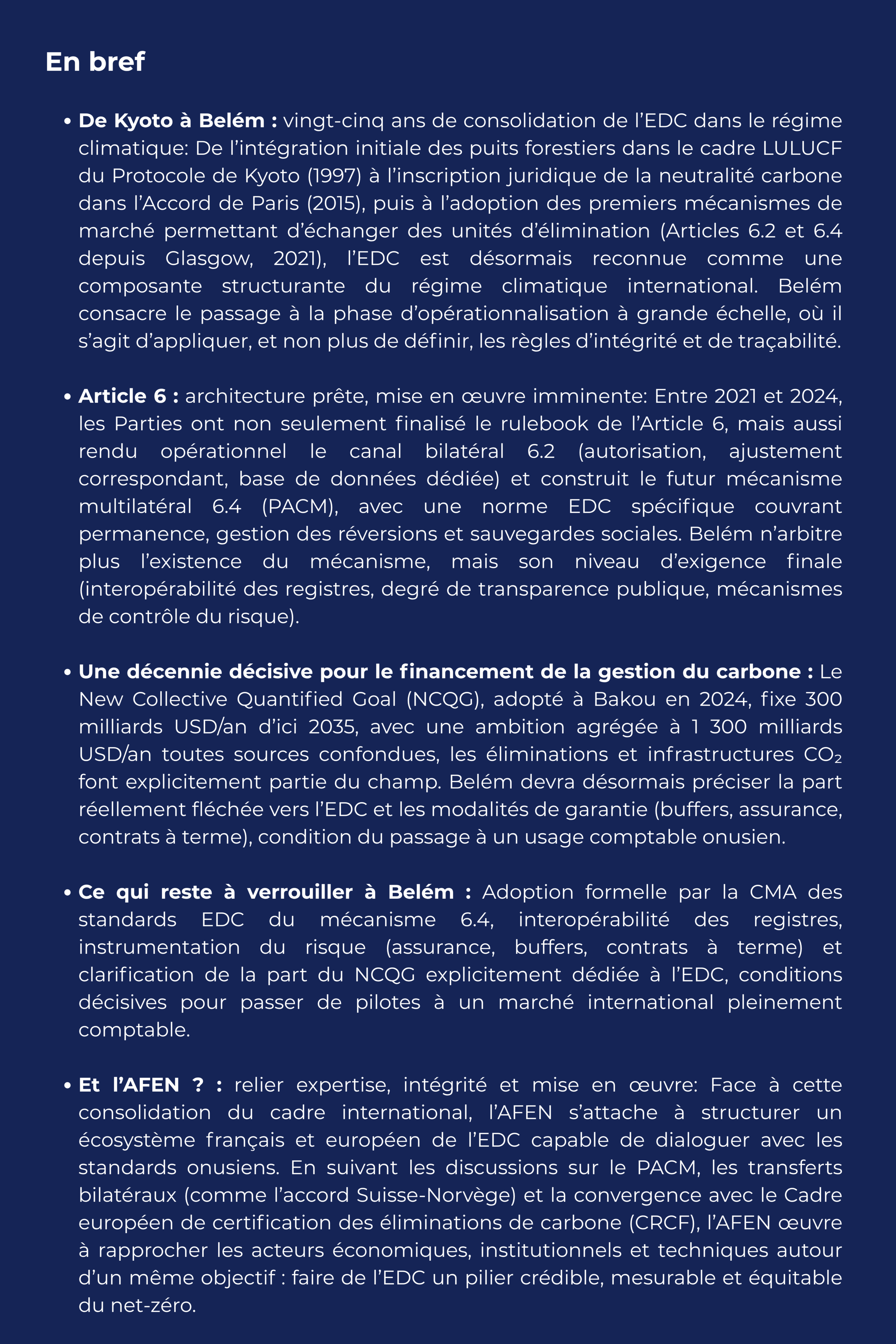

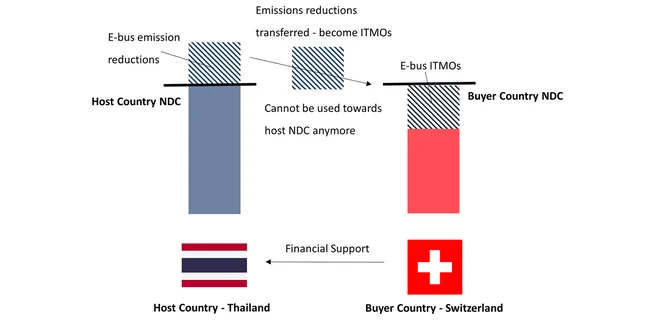

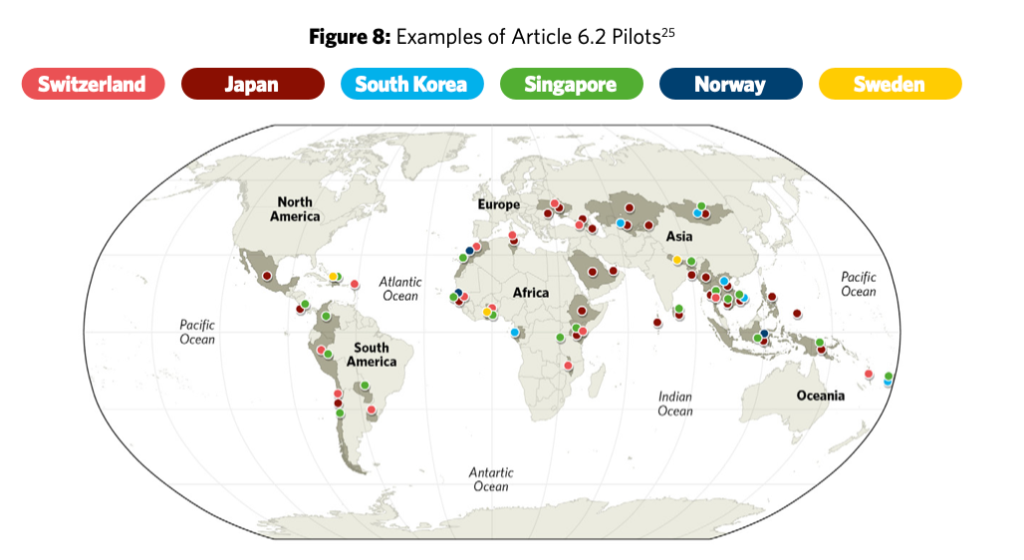

Article 6.2 establishes a framework for bilateral cooperation. where Parties can transfer reduction units or CDR, provided they comply with three principles: environmental integrity, transparency and corresponding adjustment in their national balance sheets. The UN does not authorize projects; it merely verifies that national reports comply with these principles. Between 2021 and 2024, over twenty countries have launched programs within this framework, often between industrialized countries and partners in the South. Switzerland has been a pioneer, with eleven bilateral agreements covering volumes of around 20 MtCO₂ by 2030, while states such as Sweden, Japan and Singapore have followed suit.

Article 6.4 establishes a multilateral UN mechanism, the future Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM), placed under the direct supervision of the GCA, with the explicit aim that each credit should represent one tonne of CO₂ effectively and sustainably removed. Unlike the Clean Development Mechanism, it gives the UN a formal role as validation, registration and post-crediting monitoring authority.

Between 2021 and 2024, theSupervisory Body has adopted a first generation of foundational technical standards, which define in particular :

- an official, unified definition of CDRincluding natural and technological solutions

- the long-term monitoring obligationwell beyond the initial granting of credit;

- a buffer pool mechanism to automatically compensate for any involuntary loss (fire, leakage, etc.);

- direct responsibility of the project owner in the event of avoidable loss, with compulsory cancellation of equivalent credits.

These standards, technically finalized in Baku (COP29) in the documents Standard on Methodologies and Standard on Removalsare the complete operational base of the future PACM. Their formal political validation by the CMA expected in Belémpaving the way for first official registrations of UN disposal projects.

At the same timeCOP29 strengthened theArticle 6.2 (bilateral cooperation) by making it compulsory to :

- ex-ante authorization by the states concerned prior to any transfer of ITMOs;

- publication of detailed technical information (methodology, MRV, nature of reduction/removal) ;

- registration in an international register Article 6guaranteeing public traceability;

- and the mandatory application of a corresponding adjustment in national climate inventories, ensuring there is no double counting between countries.

In addition, COP29 is the new quantified collective climate finance target (NCQG) : the Parties undertake to mobilize 300 billion USD per year by 2035with ambition aggregated at 1,300 billion USD per year from all sources (public and private). This ramp-up should make it possible to finance mitigation, adaptation and carbon management (CCS/CDR) at the same time.

Towards the first bilateral transfers?

Since 2021, the bilateral cooperation provided for under Article 6.2 has no longer been theoretical: it is now translated into concrete operations. In June 2025, Switzerland and Norway will realized the first international transfer of ITMOs from permanent removals, based on the geological storage of CO₂ in the North Sea, a historic milestone for UN accounting of "net negative" units.

The pilot involves an initial volume announced at between 1,000 and 10,000 tCO₂, with a gradual ramp-up. Inherit (Norway) acts as supplier of permanent CDR, while a pool of Swiss buyers (Swiss Re, UBS, Swiss International Air Lines, PostFinance, Zürcher Kantonalbank...) secures the offtakes.

This operation, to which ClimeFi contributed (a founding member of AFEN), confirms the technical, accounting and legal feasibility of permanent removal transfers under UN supervision. The next steps will mainly involve verifying the permanence and robustness of MRV over time, to enable replication on a larger scale.

Companies involved in EDC's first ITMO exchange

What's next? The challenges of Belém and the consolidation of CDR markets

COP30, to be held in Belém (Brazil) in November 2025, will have to transform a still theoretical framework into a fully operational mechanism integrating CDR into the implementation of the Paris Agreement. After the methodological consolidation in Baku in 2024, the challenge will be to move from text to application: guaranteeing the environmental credibility of transfers and organizing their large-scale financing.

The first challenge will be the effective implementation of the 6.4 mechanism, pillar of the new UN carbon market. The technical standards adopted by the Supervisory Body (permanence, verification, carbon loss management) will have to be formally validated by the CMA, paving the way for the first projects to be certified under the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM). The methodologies will cover both natural and technological removals, with post-crediting monitoring and permanence guarantees. The transfer of old projects of the Clean Development Mechanism will be strictly limited: only about 320 MtCO₂ are eligible4 Gt of historical credits, to avoid diluting the integrity of the new system.

The second challenge will be to ensure financial consistency. The New Collective Quantified Target (NCQG) will need to be clarified, including the sectoral breakdown of these flows and the share allocated to carbon management, particularly for developing countries where investment needs in CO₂ infrastructure are major. Discussions will focus on guarantee instruments (financial buffers, insurance, forward contracts) and the transparency of flows allocated to removals.

The third pillar will be the updating of the NDC 2035. Parties should clearly separate reductions and removals, and specify the volumes targeted for each category. Several developed countries, including the EUJapan and Canada, plan to include for the first time, technological CDR targets, in net-negative trajectories after 2050. Harmonization of reporting, monitoring formats, corresponding adjustments, LULUCF inventories, is expected to guarantee the coherence of the next Worldwide review.

At the same time, bilateral cooperation will continue to expand. The Switzerland-Norway agreement, the first official transfer of sustainable removal ITMOs, will serve as a model for other countries. The Carbon Management Challenge, now over twenty-five states strong, aims to coordinate the industrial development of CCS on a gigatonne scale. The European Union, through its Carbon Removal Certification Framework (CRCF, see our article), will seek to align its integrity criteria with those of the PACM to ensure compatibility between markets.

Beyond the technical aspects, Belém will have to decide two foundational questions These include: how to link the ramp-up of the CDR with the phase-out of fossil fuels, and how to distribute the economic and technological benefits of the CDR equitably between North and South. The success of COP30 will depend on the Parties' ability to make the CDR credible, traceable and fair, transforming it from a simple compensation tool into a genuine industrial pillar of global net-zero.

Conclusion

In the run-up to COP30, the CDR is no longer a technological gamble, but a recognized pillar of the international climate framework. With an Article 6 framework now ready to be activated, a clearly defined global financial target and the first transfers of negative units already underway, the CDR is entering a phase of real operationalization, at the direct intersection of climate, industrial and sovereignty dynamics.

For AFEN, this marks not just an institutional transition, but the beginning of a process of accountability: helping to create a French and European ecosystem capable of aligning with UN standards, securing environmental integrity and enabling credible and equitable scaling-up. By supporting the first transfers, anticipating alignment with the PACM and CRCF, and building the capacity of players, AFEN intends to play an active part in building a robust, traceable and sustainable carbon economy, fully compatible with global net-zero.

written by Raphaël Cario