I. Why is CDR necessary?

Limiting global warming to 1.5°C, as set out in the Paris Agreement, means not only drastically reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but also removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In 2022, CO₂ emissions reached 40 Gt CO2 ₂an all-time record. If all greenhouse gases are added, the total climbs to 53.8 Gt CO2 eq. To get 50% chance of limiting warming to 1.5°Cwe estimates that only 250 GtCO₂ are left to be emitted from 2020. This corresponds to ≈6 years of emissions at current rate. For 2°C, the budget is around 1,150 GtCO₂or ≈25 years at the current rate.

Article 4.1 of the 2015 treaty speaks explicitly of achieving "a balance between anthropogenic emissions and removals by sinks" in the second half of the century (UNFCCC). This balance can only be achieved with thecarbon removal (CDR). So-called "residual" emissions (aviation, cement, agriculture) are technically or economically impossible to remove completely. To offset these flows, it will be necessary to develop technological or biogeochemical carbon sinks capable of storing CO₂ on a long-term basis.

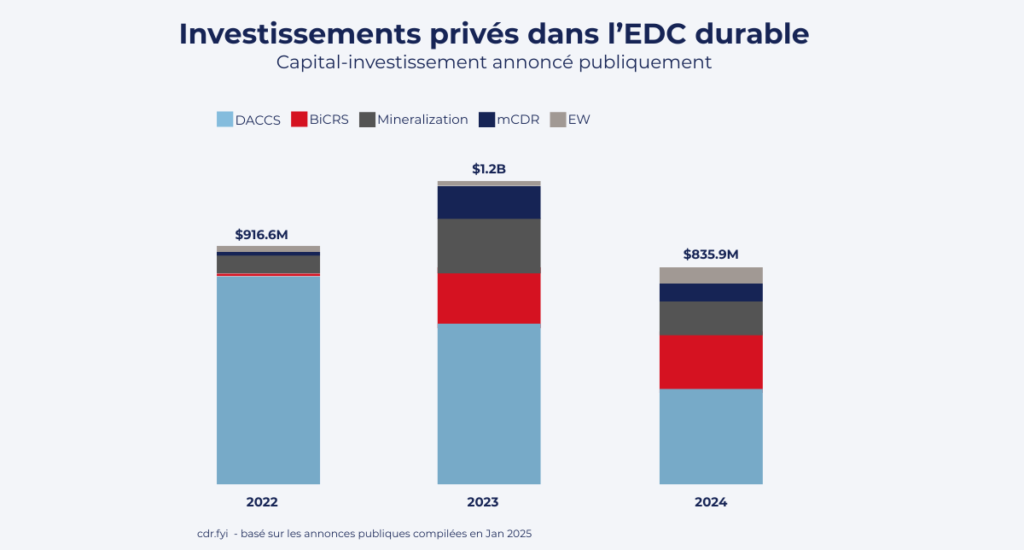

The latest IPCC report estimates that scenarios compatible with 1.5 °C require 7 to over 10 GtCO₂/year of removal by 2050. Today, the volume of CDR actually delivered is derisory: ≈1.3 MtCO₂/year according to the 2024 edition of State of Carbon Dioxide Removal. In other words, less than 0.1% of what should be achieved within three decades.

The gap is colossal, and calls for a real industrial effort to move from megatons today to gigatons in 2050. involves industrial, infrastructure and financing policies on a massive scale.

II. Where do we stand today? Capacity, national policies and the market

1) Global deployment and technology mix

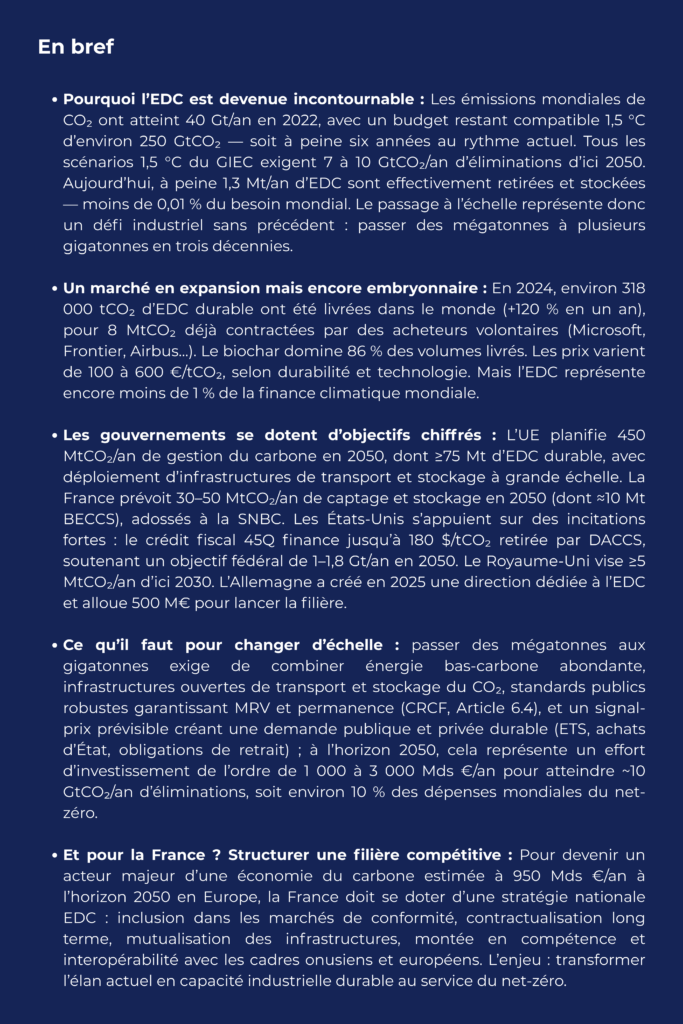

Independent monitoring data (including cdr.fyi) indicate that in 2024, about 318,600 tonnes sustainable CDR have actually been delivered to buyers (i.e. +120% vs. 2023), while 8 MtCO₂ have been contracted. The dominant technology is the biocharwhich represents approximately 86% of 2024 deliveries.

Alongside these projects BECCS (bioenergy with capture and storage) and DACCS (direct air capture with storage) are multiplying, but actual volumes remain low despite growth. L'enhanced weathering remains in the pilot phase. In particular, there is a diversification of technologies, dominated by DAC until 2022.

2) National objectives and plans

In addition to the first large-scale projects and the voluntary market, a number of major economies are beginning to establish quantified trajectories for carbon capture and CDR. These national strategies translate into public policy the scale of the volumes required between now and 2030-2050, and send out a strong signal to investors and project developers.

- France. France National Low Carbon Strategy provides for a ramp-up in carbon removal: around 10 MtCO₂/year via BECCS in 2050, integrated into an overall target of 30-50 Mt/year of capture and storage (all sources combined). To achieve net neutrality, France is also counting on natural sinks - nearly 35 Mt removed by forests, 20 Mt by wood products and 10 Mt by agricultural land - to offset residual emissions estimated at nearly 80 MtCO₂e. The country relies on a CCUS roadmaptransport and storage infrastructures, and on the Low Carbon Label, a pioneer in Europe for the voluntary CDR market.

- European Union. The CRCF (The European framework for certification of carbon removals, see our analysis) is adopted (2024). The "Industrial Carbon Management" strategy (2024) anticipates ≈450 MtCO₂/year captured and stored/upgraded by 2050 (incl. CCUS) and laid the foundations for a network of transport/storage open and cross-border. In 2024, the Commission recommended a target of -90% net emissions by 2040 compared with 1990, implying ≈400 MtCO₂/year of removals by this horizon (including LULUCF with 75Mt of sustainable CDR).

- United Kingdom. Targetat least 5 MtCO₂/year of CDRs engineered by 2030with supporting business models (contracts for difference, etc.).

- United States. On the federal side, the strategy and official analyses place the role of removals at ~1-1.8 GtCO₂/year in 2050 (programmatic order of magnitude). The DAC hubs planned by IIJA ($3.5 bn for 4 hubs) were suspended at the beginning of 2025, creating short-term execution uncertainty (see Reuters). On the other hand, the tax credit 45Q remains in force: up to $180/tCO₂ for stored DAC and $85/t for BECCS, significantly improving project bankability. A 10,000 tCO₂/year DACCS project generates, thanks to the 45Q credit set at 180 $/t, around $1.8 million per year. The scheme applies for 12 years, thus ensuring $21.6 million of guaranteed income over the life of the loan. Assuming a CAPEX range of 5,000 to 10,000 $/t capacity (i.e. ≈$50-$100 million initial investment), this $21.6 million covers ~22% to ~43% of CAPEX.

- Germany. Climate neutrality in 2045 and net-negative after 2050 are just two examples. enshrined in law with residual emissions to be offset in 2045 of 49 to 229 MtCO₂e/year. The law requires ≥40 Mt/year of LULUCF wells. This will leave 25 to 180 Mt/year to be processed by technological CDR. A dedicated CDR department was created in 2025 and the German Parliament adopted in November 2025 a 476 M€ budget for the durable CDR, including 156 M€ from 2026. This budget refines the envelopes previously mentioned (up to 500 M€ by 2033) and represents the first national financial commitment clearly earmarked for CDR.

Voluntary purchases are on the rise: by 2024, more than 8 Mt of CDR credits were purchased by companies such as Microsoft, Shopify or Frontier. But most deliveries are scheduled between 2025 and 2030.

3) Financial support

Public support is structured. For example: Between 2020 and 2023, excluding funding from member states, the EU has allocated around 657 million euros in direct support for CDR methods through existing programs such as Horizon Europe. Carbon Gap list European financial support and existing opportunities (nearly 70 by September 2025).

This support focuses mainly on three areas the research and technological maturation (via Horizon Europe, in particular for improve TRLs and develop robust measurement and certification methodologies), dindustrial demonstratorss and projects première-of-a-kind (notably via the Innovation Fund), as well as CO₂ transport and storage infrastructures considered to be mutualized between CCS and CDR (financed via the European Interconnection Facility).

On the scale of EU climate budgets, estimated at around 700 billion euros for the 2028-2034 period under the horizontal objective of 35 % of the European budget dedicated to climate action, the amounts explicitly earmarked for the CDR remain marginal, at €657 million according to CarbonGap i.e. less than 0.1 %, which underlines both a nascent dynamic and the need to move rapidly towards demand-creating instruments (European public purchasing) rather than technological support alone.

III. What are the conditions for scaling up?

1) Technological and industrial conditions

The successful ramp-up of the CDR depends on a number of technological conditions that are already taking shape.

First of allA low-carbon energy source that is both abundant and competitive. The IEA stresses that less than 2% of the world's electricity production in 2050 would be sufficient to power gigatonne-scale CDR capacity. The continuing decline in solar and wind power costs, combined with the rise of geothermal energy and industrial waste heat networks, is creating an energy base that facilitates the large-scale deployment of technologies such as DACCS, BECCS and accelerated weathering.

The second favourable condition is the structuring ofCO₂ transport and storage infrastructures. The European Union is ahead of the game with its " Industrial Carbon Management "(2024), which provides for 50 MtCO₂/year of injection capacity by 2030, 280 Mt in 2040 and 450 Mt in 2050. These figures are credible because they are based on a geological storage potential assessed by the Joint Research Center à several hundred gigatons.

A key factor is the deployment of integrated industrial hubs (low-carbon energy, capture, transport, storage) to Rotterdam, Antwerp, Dunkerque or Le Havre. In Rotterdam, Porthos is aiming for 2.5 MtCO₂/year by 2026 (≈37 Mt over 15 years). In Antwerp, theAntwerp@C CO₂ Export Hub starts at 2.5 Mt/year, with an ambition to reach 10 Mt/year by 2030. In Dunkirk, an initial phase of 1.5 Mt/year as of 2028 (Lhoist Réty + Eqiom Lumbres) will supply a terminal expandable to 4-5 Mt/year, supported by Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) funding of up to €189 million. Norway, Northern Lights starts H2-2025 (1.5 Mt/year, extension to ≥5 Mt/year validated in 2025). Shared networks reduce unit costs through economies of scale and are a pillar of the European Carbon Management Strategy.

2) Governance, standards and certification

The credibility of the CDR is based on trust. Unlike renewables, where the kilowatt-hour produced is instantly measurable, the "ton removed" of CO₂ is only valuable if it can be shown that it has been captured, stored and will remain out of the atmosphere for centuries. This implies three conditions: robust MRV (measurement, reporting, verification) protocols, a guarantee of permanence, and a strict exclusion of double counting.

These standards are becoming increasingly structured, both in Europe and worldwide.

- In Europe, the CRCF adopted in 2024, is the world's first regulatory attempt to certify large-scale CDR. It defines sustainability criteria (permanence > 100 years to be considered "sustainable"), harmonized MRV rules across the EU, and a registry to ensure traceability.

- Internationally, theArticle 6.4 of the Paris Agreement is overseen by a UN body that must establish robust standards for international carbon credits.

- While we wait for public frameworks to be put in place, private standards have taken the lead. For example, Puro.earth (Finland, Nasdaq-listed): more than 1,000,000 tCO₂ certified since 2019.

For the CDR to attract the billions of $/year needed, the "tonne" must be recognized as a secure financial asset. This requires public-private convergence to reduce costs and increase confidence.

3) Financing requirements and business models

The total cost of the CDR by 2050 will be trillions. At 100 €/tCO₂withdrawing 10 Gt/year would represent ≈€1,000 billion/year ; à 300 €/tthe bill rises to ≈€3,000 billion/year.

Today, the world invests around $5,500 billion/year in physical assets related to energy, transport and industry. According to McKinsey (2022)9,200 Md$/year by 2030-2050 to reach net-zero - an increase of around $3,500 billion/year, or +65 %. In this context, devoting $1,000 to $3,000 billion/year to CDR would only represent around 10 % of this future global effort, which remains proportional to the important role that the IPCC scenarios attribute to carbon removal technologies.

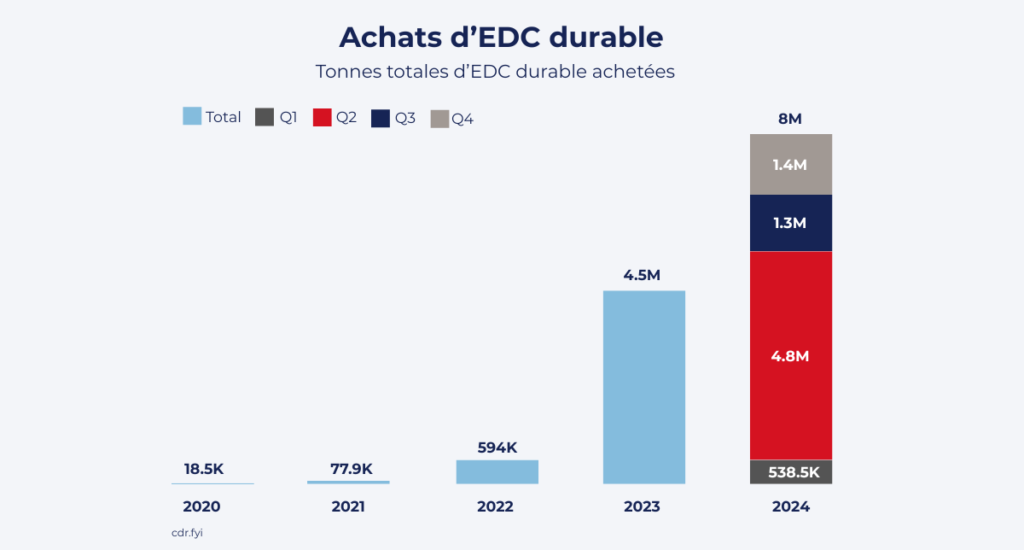

The current gap is huge: in 2024, the CDR will have captured just under $0.85 billion of private financing against $1,300 billion of total climate finance. This means that the CDR currently weighs less than 0.1% of climatic finance volumes.

The challenge is not whether the world can mobilize this capital - it is already doing so for energy - but how to direct a fraction of existing flows towards the CDR. This means securing sustainable revenue models : long-term voluntary purchases (e.g. Microsoft, Frontier), integration into compliance markets (e.g. EU ETS), and public instruments (45Q tax credits, Innovation Fund, ITC Canada).

To reach this scale, several business models are emerging:

- Voluntary purchases and long-term contractsThese are useful for kick-starting the industry (e.g. Microsoft or Frontier). Microsoft represents 70% of the total CDR volume contracted, or 5.1 million tonnes, and has already committed nearly 25 MtCO₂ since 2020. Its acquisitions are mainly based on long-term contracts deliverable between 2030 and 2050. The Group Frontier (Stripe, Alphabet, Shopify, Meta, McKinsey) has launched a commitment to purchase at least $1 billion worth of permanent CDR between 2022 and 2030. Offtakes include 153,000 t with Vaulted Deep for $58.3 million, 112,000 t with Charm Industrial for $53 million, and tens of thousands of tons with Heirloom, Lithos and others.

- Integration into compliance marketssuch as the EU ETS for the 2030-2040 horizon, like the recommends the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change (our analysis).

- Public policies These include tax credits (45Q in the USA, ITC in Canada), subsidies (EU Innovation Fund), withdrawal obligations and residual emissions taxes.

Conclusion

The challenge is no longer to demonstrate the usefulness of CDR, but to secure its industrialization: predictable demand, open transport-storage infrastructures, MRV integrity and permanence. We need to move from isolated projects to bankable portfolios where prices, volumes and responsibilities are clear.

Today, France needs a national CDR strategy, anchored to the SNBC, that sets a clear trajectory for volumes and price signals, plans and opens up CO₂ infrastructures, establishes a single, interoperable integrity framework, creates a legible and stable investment environment, develops skills and innovation, and organizes international coordination as well as public accountability. The aim is simple: to provide visibility, reduce risk and transform scattered pilots into a competitive, sustainable industrial sector.

AFEN's mission is to structure the industry: federate developers and buyers, push for standardization of MRV contracts and practices, and enlighten public authorities on the role of the CDR and scaling up. By mobilizing this ecosystem around a clear strategy, France can convert the current momentum into sustainable industrial capacity - with, by 2050, an estimated economic potential of ~50 Bn €/year and up to ~130,000 jobs for France (on a European market ~225 Bn €/year and a global market ~935 Bn €/year),in accordance with the BCG × AFEN ratio.

written by Raphaël Cario